The Troubling Tale of France's Premier President

Blog by

Last updated: Wednesday June 12th, 2024

Report this blog

Last updated: Wednesday June 12th, 2024

Report this blog

+3

Quick Links

This blog shall provide an academic overview of the background, course of events and fate of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte's presidency (1848–1852). It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

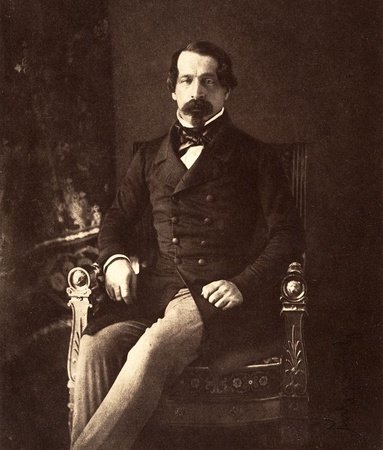

Daguerreotype of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte in 1852, his last year as president before proclaiming himself Emperor of the French.

Overview

On 10th December 1848, after one-and-a-half millennia of monarchical sovereignty since Clovis I assumed the role of King of the Franks in 481, [1] France inaugurated its first definite non-monarchical ruler, [2] Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte (1808–1873). The nephew of Emperor Napoleon I, he had previously attempted to restore the Bonapartist dynasty through a coup d’état twice, in 1836 and 1840. Bestowed the timeous opportunity eight years later in the aftermath of the February Revolution and subsequent promulgation of the Second French Republic, he contested the 1848 presidential election and triumphed decisively.

Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte's presidency, relatively prosaic and vacuous, was destined to provoke his ambition to emulate his foregone uncle’s unparalleled success. Indeed, he would not content himself with a mere four years and sought to prolong and asseverate his authority, which materialised after his 1851 coup d’état, proclaiming himself emperor the following year. His four insipid years as president, themselves the product of a frangible political order, were not much more than a road for the restoration of French authoritarianism as had happened with Napoleon I’s centralisation of power after the Coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799, culminating in his self-coronation as emperor in 1804. His nephew was not far removed from him.

Founding The Second Republic

The presidential Second Republic arose from the ashes of the 1848 French Revolution (February Revolution)—a slew of obloquy to the recalcitrant monarchical status quo existing since Napoleon I’s downfall in 1815. In February 1848, following Prime Minister François Guizot’s prohibition of the liberal campagne des banquets, Paris detonated in belligerent protest to the Orléanist regime under King Louis Philippe I, itself born of a revolution (the 1830 Trois Glorieuses). After three decades of despotism, [3] first from the House of Bourbon and then from that of Orléans, the working and middle-class masses finally lost faith in the legitimacy of a French monarchy. The king abdicated at the revolution’s apex, paving the path for the establishment of a republican government representative of the populace’s will. [4]

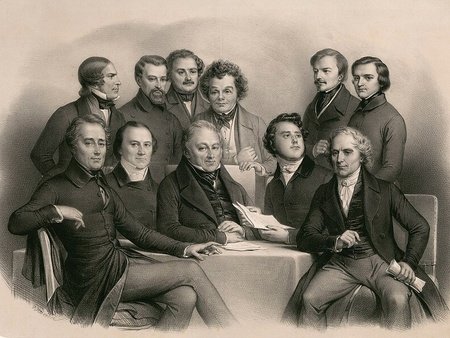

The same day, on 24th February 1848, the provisional government cemented political control, under the collective leadership of three factions: Moderate Republicans (including the prime minister Jacques-Charles Dupont de l’Eure), Radical Republicans (including state minister Ferdinand Flocon) and Socialist Republicans (including state minister Alexandre Martin [5]). It enacted considerable progressive reforms—consolidating the Luxembourg Commission as a potent political entity, abolishing slavery in French colonies and re-empowering the working-class National Guard first established during the 1789 Revolution—until being dissolved in May.

Protestors burning regalia during the 1848 February Revolution indirectly deposing the last French King, Louis-Philippe I, after which a republican government was founded.

The government was generally perceived as ineffective, convulsive and extremist, especially by the neglected middle class, which the predominant Moderate Republicans sought to appease. Nor was it popular among the disgruntled working class; economic hardships persisted—aggravated by the newly imposed forty-five-cent tax—and employment schemes provided minimal working opportunities and miserable wages. Worse yet, agrarian workers and peasants, still comprising a majority of France’s population at that point, had seen virtually no improvement in their living conditions; food prices remained unaffordable and abuse from landlords, reminiscent of feudalism, faced little legal or executive abrogation. In fact, the April legislative elections produced a sweeping Moderate Republican majority of six hundred seats, with the Socialist Republicans (Montagnards) obtaining a mere eighty. [6] The Moderate Republicans subsequently disbanded the Provisional Government in May, replaced by an Executive Commission under François Arago’s leadership, similar in structure to the 1795–1799 Directory.

Categorically controlled by the Moderate Republicans, it sought to rid the Second Republic of radical and socialist influences, perceived as harbingers of mob rule. This fear was perhaps not unwarranted, especially after the Demonstration of 15 May—an attack on the Constituent Assembly organised by the socialist revolutionary Auguste Blanqui. Besides, public discontent at the grievous economic status quo was directed at the Montagnards, whose socialist ideals such as Louis Blanc’s proposed "right to work", perpetuated social and political instability. However, the proletariat did not particularly pamper the Moderate Republicans either as they hankered for socialist measures—but in an appropriate fashion, unlike the Montagnards’ maladroit approaches. Working-class ameliorations were not delivered upon; the Luxembourg Commission was annulled, socialist insurrectionists Armand Barbès and A. Blanqui were imprisoned, and unemployment soared. The last of these expedited the Executive Commission’s demise.

Categorically controlled by the Moderate Republicans, it sought to rid the Second Republic of radical and socialist influences, perceived as harbingers of mob rule. This fear was perhaps not unwarranted, especially after the Demonstration of 15 May—an attack on the Constituent Assembly organised by the socialist revolutionary Auguste Blanqui. Besides, public discontent at the grievous economic status quo was directed at the Montagnards, whose socialist ideals such as Louis Blanc’s proposed "right to work", perpetuated social and political instability. However, the proletariat did not particularly pamper the Moderate Republicans either as they hankered for socialist measures—but in an appropriate fashion, unlike the Montagnards’ maladroit approaches. Working-class ameliorations were not delivered upon; the Luxembourg Commission was annulled, socialist insurrectionists Armand Barbès and A. Blanqui were imprisoned, and unemployment soared. The last of these expedited the Executive Commission’s demise.

The members of the provisional government lasting from February to May 1848, succeeded by the Executive Commission of François Arago, later replaced by an autocracy under General Cavaignac. The frequent change in governmental system reflected the Second Republic's instability and, arguably, incompetence.

Starting from the Second Republic’s inauguration, the government provided for public works professions through membership in National Workshops to remedy unemployment. Urban masses scampered to these workshops and received a meagre, but sufficient, daily salary of two francs for undertaking light labour. However, to forestall an oversaturation of jobs risking undesired competition with private industries, many were not required to work at all, earning pay solely to placate them. The National Workshops were effective—half of Paris’ working population enlisted—but F. Arago’s Executive Commission denounced them as an unjust, tawdry solution to working class issues, considering pay was provided for no labour.

They were officially abolished in June, putting hundreds of thousands out of employment and receding the “right to work”. The proletariat immediately rose in rampant rebellion, dubbed the “June Days”, coercing the Executive Commission to disband in place of a military dictatorship helmed by General Louis-Eugène Cavaignac. Strident military intervention quelled the uprising, terrorising citizens such that no mass protests would re-emerge in 1848. General Cavaignac’s cabinet consolidated near-absolute authority to inhibit further political factionalism and volatility until democratic elections could be held in December.

They were officially abolished in June, putting hundreds of thousands out of employment and receding the “right to work”. The proletariat immediately rose in rampant rebellion, dubbed the “June Days”, coercing the Executive Commission to disband in place of a military dictatorship helmed by General Louis-Eugène Cavaignac. Strident military intervention quelled the uprising, terrorising citizens such that no mass protests would re-emerge in 1848. General Cavaignac’s cabinet consolidated near-absolute authority to inhibit further political factionalism and volatility until democratic elections could be held in December.

Colourised daguerreotype of Parisian barricades erected during the June Days uprising expediting the fall of the Executive Commission. It highlighted the proletariat's discontent at the Second Republic's inefficacy; the Moderate Republican authorities could not muster support from any voting base.

The second half of 1848 nested an unabashed repudiation of the Moderate Republican values of liberalism and democracy vivaciously envisioned after the February Revolution—the long-awaited opportunity for France’s lower class to achieve emancipation. Yet, English professors O. E. and C. M. Heywood assert that ‘by June its hands were indelibly stained with the blood of Parisian workers’ and ‘clearly this was a regime that was not short of enemies’. For the rest of 1848, King Louis-Philippe I’s despotic tendencies seemed to resurface as most left-wing publications were shut down, working-class protestors were deported to the colony of Algeria and the Constituent Assembly was disempowered.

So far, the Second Republic proved nothing short of a fiasco; in the first chapter of his essay The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Karl Marx famously declares that historical events occur twice: ‘the first time as tragedy, the second as farce’. He specifies in excoriating the republic’s structure: ‘the Revolution of 1848 knew nothing better to do than to parody [that of 1789]’, labelling L. Blanc a meagre mock of Maximilien Robespierre and the Montagnards a feigned fabrication of their 1793–1795 forerunners. December, hosting the national presidential elections—the culmination of governmental efforts—would provide the republic with the invaluable opportunity to redeem itself and evince its liberal, democratic status.

So far, the Second Republic proved nothing short of a fiasco; in the first chapter of his essay The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Karl Marx famously declares that historical events occur twice: ‘the first time as tragedy, the second as farce’. He specifies in excoriating the republic’s structure: ‘the Revolution of 1848 knew nothing better to do than to parody [that of 1789]’, labelling L. Blanc a meagre mock of Maximilien Robespierre and the Montagnards a feigned fabrication of their 1793–1795 forerunners. December, hosting the national presidential elections—the culmination of governmental efforts—would provide the republic with the invaluable opportunity to redeem itself and evince its liberal, democratic status.

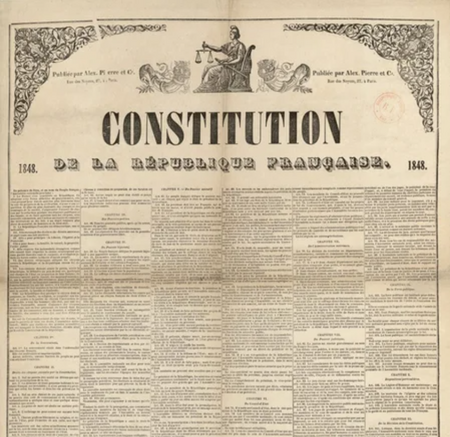

Representation of the French Constitution of 1848 promulgated in November, mandating universal suffrage—all adult male citizens aged over twenty-one could participate in national and local elections. The 1848 presidential election would be the first of its kind held under universal suffrage since the inaugural election of the First Republic in 1792.

Presidential Election

Partially inspired by the American model popularised in sociologist Alexis de Tocqueville’s study Democracy in America, the Second Republic was to be led by a democratically elected president, with quadrennial elections held under universal male suffrage. Ever since the First Republic, suffrage had been limited to the bourgeoisie or upper classes, lopsidedly disfavouring progressive candidates appealing to the lower class masses. Most legislative elections from 1815 to 1848, with under one per cent of the population enfranchised, produced staunch pro-monarchy majorities; the Second Republic demanded an equitable model truly representative of the people’s will.

The Constitution of 1848 guaranteed that: ‘All Frenchmen aged twenty-one, and in the enjoyment of their civil and political rights, are electors’ (Article 25). The president, whilst wielding strong executive authority such as controlling the armed forces, could only serve one four-year term and had to collaborate with a parliament, the National Assembly, comprising seven hundred fifty members renewed every three years. Besides those political, numerous social freedoms were bestowed, including of religion, association, a free press, conscience and property. It paralleled the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen drafted during the 1789 Revolution, enshrining popular sovereignty: ‘The sovereignty exists in the whole body of French citizens. It is inalienable and imprescriptible’ (Article 1). Socialist influences partially permeated, recognising the prevalence of class struggles as declared in the preamble: ‘The burdens and advantages of society shall be more and more equitably apportioned, to augment the comfort of every individual by the gradual reduction of the public expenses and taxes’. The Constitution of 1848 was promulgated in November, one month before the inaugural presidential election.

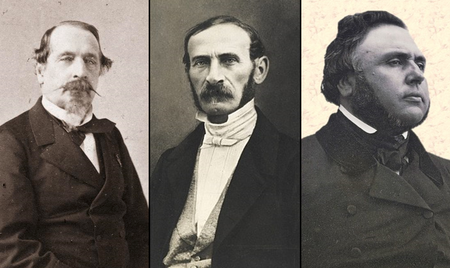

The three main candidates of the 1848 French presidential election: Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of Emperor Napoleon I, General Louis-Eugène Cavaignac, military dictator from May to December 1848, and Alexandre Ledru-Rollin, socialist member of the Executive Commission from May to June 1848.

Two leading established candidates sprung up: the Moderate Republican General Cavaignac and Montagnard Alexandre Ledru-Rollin. [7] Both were deeply disapproved throughout France: the former for rescinding workers’ rights and spearheading a military dictatorship and the latter for his unbridled radicalism and association with the June Days. Most rural residents were not even aware of their candidacy, as they myopically concentrated on urban issues. Conservatives—pious Catholics and monarchists (Orléanists and Legitimists [8])—could not assent to such anti-clerical, republican politicians. These disgruntled voting bases therefore turned to a somewhat dark horse figure, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, who was not recognised by his accomplishments but certainly by his surname, automatically rendering him the most famous of the three candidates.

He was politically unaffiliated, running a masterful campaign as a centrist, neither socialist nor reactionary, committed to the recognition of fundamental liberties and the eradication of poverty—the emancipation of both workers and farmers from social and political injustice. His pamphlet “The Extinction of Pauperism” was widely circulated and appreciated by the lower classes disenchanted by the Second Republic’s inefficacy on economic issues. Many politicians, most notably, Adolphe Thiers, propped up his candidacy, convinced that he could later be manipulated and swayed to enact their propositions heedlessly. Most pundits presaged Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s victory, but the results were inordinately one-sided: he won nearly three-quarters of the national vote—all urban departments [9] and ninety per cent of the vote in many rural departments—whereas the Moderate and Socialist Republicans, establishing the Second Republic in the first place, collectively won a measly four of eight-three departments. Whilst Louis-Napoleon had virtually vanquished the Republican opposition, the National Assembly was still dominated by the opposition, portending the obstacles to his political agenda overshadowing his presidency.

He was politically unaffiliated, running a masterful campaign as a centrist, neither socialist nor reactionary, committed to the recognition of fundamental liberties and the eradication of poverty—the emancipation of both workers and farmers from social and political injustice. His pamphlet “The Extinction of Pauperism” was widely circulated and appreciated by the lower classes disenchanted by the Second Republic’s inefficacy on economic issues. Many politicians, most notably, Adolphe Thiers, propped up his candidacy, convinced that he could later be manipulated and swayed to enact their propositions heedlessly. Most pundits presaged Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s victory, but the results were inordinately one-sided: he won nearly three-quarters of the national vote—all urban departments [9] and ninety per cent of the vote in many rural departments—whereas the Moderate and Socialist Republicans, establishing the Second Republic in the first place, collectively won a measly four of eight-three departments. Whilst Louis-Napoleon had virtually vanquished the Republican opposition, the National Assembly was still dominated by the opposition, portending the obstacles to his political agenda overshadowing his presidency.

Results of the 1848 French presidential election.

Domestic Policy

Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s domestic policy undertakings were circumscribed by his brief tenure and persistent contrariety with the National Assembly’s opposition. As a moderate and not a left-wing firebrand, his entire parliamentary backing lay within the conservative Order Party—vociferously inimical to the republican course of events in 1848—which he was contrived to appease. In fact, the leading Legitimist figure Adolphe Thiers deemed him a “crétin que l’on mènera” (“moron who we will lead”), and this reflected in the President’s leadership approach. His first two prime ministers from 1849 to 1851, Odilon Barrot and Alphonse Henri d’Hautpoul, were distinguished conservatives.

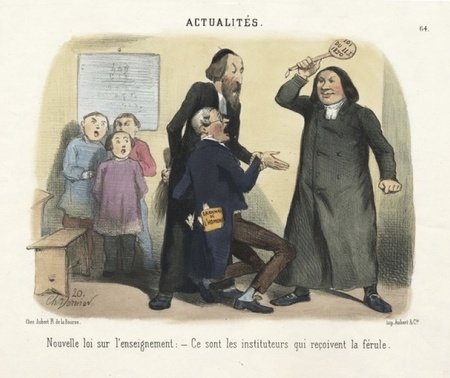

Louis-Napoleon suspended the publication of several Montagnard-leaning newspapers and curbed the freedom of association. The republican opposition was further disempowered by the 1850 Burgraves Law, partially reinstating census suffrage to exclude three million working-class citizens from the right to vote—in Paris, the electorate diminished from over two-hundred thousand individuals to a mere seventy-five thousand. That same year, he promulgated the Falloux Law favouring the establishment of schools supervised by Catholic congregations; the state and Church were pushed to an unyielding interrelationship which only thawed in the 1880s as laïcité (state secularism) became mandated. These reforms indicated a complete repudiation of everything the 1848 Constitution stood for—the government seemingly adverse to aiding working class populaces recover from their economic and social suppression under the Orléanist regime. Nonetheless, economic woes were marginally alleviated; for instance, public works spending rose by forty per cent between 1848 and 1849 and customs duties fell by twenty-five per cent.

Cartoon lampooning the 1850 Falloux Law, with a clergyman scolding two teachers to assert his authority over the school's administration.

Foreign Policy

Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte aspired to undertake lofty international engagements to rekindle France’s might as a continental superpower, but four years could not suffice. In his study Napoleon III, Irish politician John M. O’ Sullivan notes that: ‘the desire to satisfy France in one of those things for which his name stood—“glory”’. As president, he made one sole prominent foreign policy venture: intervening against the Italian Revolutions of 1848–1849—with political expediency, not “glory”, in mind. In the wake of the liberal effusion of popular sentiment combatting the intransigent conservative status quo, the Italian masses rose against their sovereigns to forge democratic nations representative of their will.

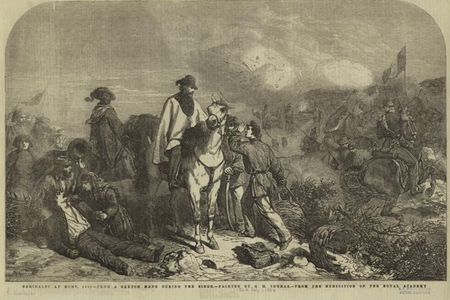

The Papal States were among the victims of the 1848 Revolutions; the scorned Pope Pius IX fearfully fled in November 1848, paving the path for a new republican government. The Roman Republic was proclaimed in February 1849, one of the steps towards Italian unification (Risorgimento), but it lay on unsound foundations, inclined to collapse with a stronger foreign power’s intervention. Eager to further appease the fervently Catholic Order Party and restore the pope, Louis-Napoleon mustered a military force to besiege the Roman Republic in April 1849. After the months-long Siege of Rome, the republic capitulated in July and Pope Pius IX returned a year later, mutilating the Risorgimento. This escapade earned the president some credibility among the Concert of Europe committed to stifling liberalism and won him favours among the Order Party but decidedly tainted his standing among Republicans in the National Assembly. Ironically, a decade later as emperor, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte would intervene in favour of the Italian republican resistance, having different political ambitions.

Italian republican commander Giuseppe Garibaldi at the Siege of Rome, the successful French attempt to restore Pope Pius IX's authority over the Papal States.

Fate

Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s domestic and foreign accomplishments over three years were generally creditable but could not hold a candle to his uncle’s transmutation of France’s social and legal customs and continental conquests, leaving him parched with disappointment. More years in power were required to quench his thirst for glory. His attempts to overturn the constitutional amendment limiting the president to one four-year term initially constituted parliamentary proposals. Louis-Napoleon’s support in the National Assembly was tenuous, especially after the 1849 legislative elections, in which the conservative Order Party obtained sixty per cent of seats and the Republicans thirty-five per cent.

Since transformative legislation such as constitutional amendments required a two-thirds supermajority to pass, most of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s aspirations had to be curtailed. Republicans unrelentingly assailed his policies, such that Montagnards, weary at the president’s refusal to nationalise industries and abolish indirect taxation such as the forty-five-cent one, organised an uprising to usurp power in June 1849, which was successfully suppressed. The president’s base of support, the Order Party, was deeply divided between Orléanists and Legitimists and only sanctioned them opportunistically, not genuinely. Indeed, the president boasted no bona fide allegiance to him in the National Assembly.

Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte's 1851 coup d'état, overriding the 1848 Constitution and the National Assembly's authority to usurp near-absolute power.

In July 1851 he called for a parliamentary vote on a constitutional amendment allowing him to run for election again the following year, rewarding him an additional four years in power; it was narrowly defeated. Unwilling to concede his ambition, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s attempts to lengthen his tenure turned illegal and violent. Mirroring his 1836 and 1840 undertakings, the president negotiated with the armed forces to garner their support and prepared to foment an insurrection. On 2nd December 1851, he initiated a successful coup d’état, temporarily suspending the National Assembly’s functions. The 1848 Constitution was scrapped and replaced by a new authoritarian one promulgated in January 1852, bestowing the president near-absolute control over legislation and military action.

In December Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte did away with the title of “president” altogether and proclaimed himself Emperor of the French. His time as emperor, mostly devoid of political opposition, was more fruitful and determined in its domestic and foreign policy undertakings, but nonetheless at odds with the liberalism sought in 1848. The Second Republic had lasted a mere four years, overpowered by the imperious auspices of one man which could not be checked effectively by the faulty, fragile political system. Emperor Napoleon III’s Second Empire would endure until his defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870; the subsequent seventy-year-long Third Republic proved assuredly coordinated, meticulously structured and puissant, overshadowing its “second” forerunner.

In December Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte did away with the title of “president” altogether and proclaimed himself Emperor of the French. His time as emperor, mostly devoid of political opposition, was more fruitful and determined in its domestic and foreign policy undertakings, but nonetheless at odds with the liberalism sought in 1848. The Second Republic had lasted a mere four years, overpowered by the imperious auspices of one man which could not be checked effectively by the faulty, fragile political system. Emperor Napoleon III’s Second Empire would endure until his defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870; the subsequent seventy-year-long Third Republic proved assuredly coordinated, meticulously structured and puissant, overshadowing its “second” forerunner.

Napoleon III as Emperor of the French in 1865.

Notes

[1] Some sources claim that Clovis I became King of Franks in 509 and was prior King of the Salian Franks, but the Frankish Kingdom was formed in 481.

[2] Whilst Napoleon I became First Consul in 1799, the title was adapted for him and not pre-assigned. On the other hand, in Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte's case, the title of “president” was specifically determined in the 1848 French Constitution.

[3] The monarchy officially returned to France after the War of the Sixth Coalition forced Emperor Napoleon I's first abdication, by which the 1814–1815 Congress of Vienna restored the House of Bourbon headed by Louis XVIII was restored. Succeeded by Charles X in 1824 who attempted to overturn constitutional limits to his authority, the Bourbon monarchy grew increasingly unpopular, culminating in the 1830 July Revolution (also referred to as the Trois Glorieuses). As a compromise between ultraroyalists and republicans, the liberal House of Orléans was established, with Louis-Philippe I crowned king in 1830. He merely proved marginally less authoritarian than his predecessor and was forced to abdicate in 1848.

[4] For a more detailed analysis of the factors behind King Louis-Philippe I's downfall, one may consider consulting my relevant blog.

[5] Alexandre Martin is also notable as the first working-class member to serve in national French politics, hence his moniker "Albert l'Ouvrier" ("Albert the Worker").

[6] The 1848 legislative elections also returned two hundred members of the conservative, monarchist Order Party (Parti de l'Ordre) to the Constituent Assembly; this would be the leading political faction following Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte's ascendancy as president.

[7] Other minor candidates contested, collectively achieving less than one per cent of the national vote: revolutionary François-Vincent Raspail as a radical Montagnard, poet and founding father of the Second Republic Alphonse de Lamartine as a Liberal, and military commander General Nicholas Changamier as a Legitimist.

[8] The Legitimists advocated the restoration of the House of Bourbon with Henri, Count of Artois, as King. They were the most conservative monarchist faction.

[9] Departments were the French electoral regions, still in place to this day. For a visual overview of the departmental results, one may consider consulting this graphic.

Bibliography

For more information, one may consider consulting these sources; I primarily used these as sources in creating this blog. They are listed in their respective categories. The links appearing throughout the blog should also be consulted.

SOURCES

- Amman, Peter (1970). “A ‘Journée’ in the Making: May 15, 1848”. The Journal of Modern History, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 42–68. Accessed via JSTOR.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Brittanica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 272–273. Accessed via Wikisource.

- Constitutional Assembly of France (1848). French Constitution of 1848. Accessed via Wikisource.

- Fasel, George W. (1968). “The French Election of April 23, 1848: Suggestions for a Revision”. French Historical Studies, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 285–298. Accessed via JSTOR.

- Fortescue, William (2004). France and 1848: The End of Monarchy. New York, United States: Routledge. pp. 99–117. Accessed via Google Books.

- Mallet, Julien. “Le Coup d’Etat du 2 Décembre 1851” [“The Coup d’Etat of December 2 1851”] (in French). napoleon.org.

- Marx, Karl (1850). The Class Struggles in France, 1848 to 1850 § Part IV. Reproduced by Marxists Internet Archive.

- ——— (1852). The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte § Chapter I. Reproduced by Marxists Internet Archive.

- O’ Sullivan, John M. (1923). “Napoleon III”. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, vol. 12, no. 46, pp. 219–232. Accessed via JSTOR.

- Online Library of Liberty (2017-06-28). “The French Government’s Budgets for Fiscal Years 1848 and 1849”. oll.libertyfund.org.

- Pilbeam, Pamela (2024). The Revolting French, 1787–1889 § Narrative of Nineteenth-Century Revolutions. Cambridge, New York, United States: Routledge. pp. 12–20. Accessed via Google Books.

- Thomas, Émile (1848). Histoire des Ateliers Nationaux [History of National Workshops] (in French). Paris, France: Michel Lévy Frères. pp. 13–34. Accessed via Google Books.

- Whitridge, Arnold. (1948). “1848: The Year of Revolution”. Foreign Affairs, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 264–275. Accessed via JSTOR.

FURTHER CONSULATION

- Apostolic Majesty (2023-03-17). “Napoleon III: The Little Emperor”. YouTube.

- Euler, Heinrich Gustav (2024-04-15). “Napoleon III”. Britannica.

- Tom Richey (2015-05-10). “Revolutions of 1848 in France (Part 2 of 5)”. YouTube.

RELEVANT SELF-PUBLISHED BLOGS

- Brainstorm (2024-05-12). “Why Did Europe Go Haywire in 1848?”. Jetpunk.

- ——— (2024-05-13). “Why Did France's Last King Fail?”. Jetpunk.

_________________________________________________________________________________

This blog is part of a set concerning 1848. The rest can be accessed from my History series.